LMArena's $100M Raise, Claude's Benchmark Surge, & Why AI Leaderboards Shape the Market

A UC Berkeley side project became the AI industry's default ranking system, and its leaderboard positions now influence which models win enterprise deals

From Chatbot Arena to a $100 Million Company

LMArena started as a research project. In 2023, a group of UC Berkeley SkyLab researchers built Chatbot Arena under the LMSYS (Large Model Systems Organization) umbrella. The concept was simple: show users two anonymous AI model responses side by side, let them pick the better one, and use the votes to generate rankings. No corporate benchmarks, no hand-picked evaluation sets. Just blind human preference at scale.

It worked, and Chatbot Arena became the industry’s most-cited AI leaderboard within months. Model labs began timing their releases around Arena rankings. Enterprise buyers started referencing Arena scores in procurement decisions. By mid-2025, the platform’s usage had surged 200% year-over-year.

The team rebranded to LMArena, graduated from LMSYS, and raised $100 million from Andreessen Horowitz. We covered the raise here. The platform moved from lmsys.org to arena.ai. What had been an academic experiment was now a business, and its rankings carry real financial weight.

How the Rankings Actually Work

LMArena uses the Bradley-Terry rating system, a statistical model originally developed for paired comparison experiments. It functions similarly to chess Elo ratings: models gain or lose points based on head-to-head human votes. When you visit arena.ai, you are shown two anonymous model responses to the same prompt. You pick the one you prefer. Your vote adjusts both models’ scores. Multiply that by millions of votes and you get a ranking that reflects aggregate human preference.

The key advantage over traditional benchmarks is that LMArena is harder to game. You cannot optimize for it the way you can memorize MMLU questions, because the evaluation is based on open-ended human preference across unpredictable prompts from real users. There is no fixed test set to overfit on.

LMArena also applies “style control” to its rankings, adjusting for the tendency of users to prefer longer, more verbose responses regardless of quality. Without this adjustment, models that pad their outputs with unnecessary detail would score higher. The style-controlled leaderboard better reflects actual helpfulness rather than superficial polish.

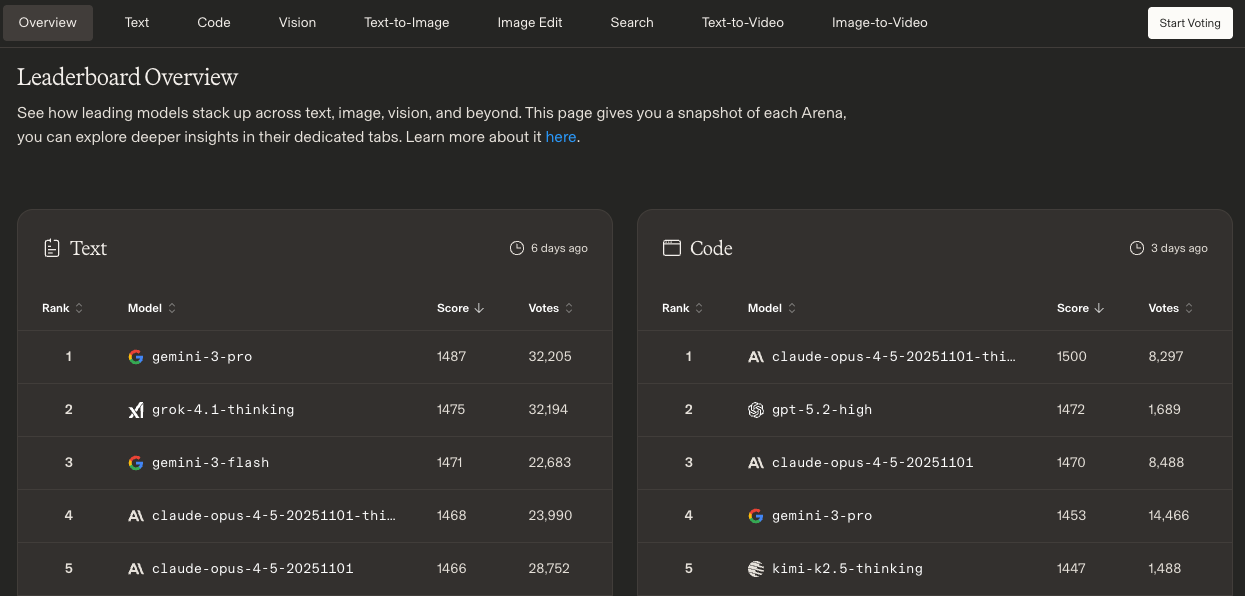

The platform now runs leaderboards across multiple categories: text (general chat), code, math, hard prompts, vision, and more. Each uses the same Bradley-Terry methodology but with category-specific prompts. This matters because a model that excels at creative writing may perform poorly on code, and the overall Elo can obscure these differences.

Where Claude Stands on the Leaderboard

As of early 2026, the LMArena text leaderboard has become a three-way race at the top. Gemini 3 Pro leads overall with an Elo score approaching 1500, making it the most broadly preferred model in blind comparisons. GPT-5.2, added to the leaderboard in December 2025, is the top performer on reasoning-specific benchmarks, particularly with extended thinking enabled. Claude Opus 4.5 holds the strongest position in coding and software engineering.

The category-specific results matter more than the overall ranking for most practical purposes. Claude Opus 4.5 was the first model to break 80% on SWE-bench Verified, scoring 80.9%. Anthropic’s coding momentum has been building since Claude Sonnet 4.5 set the standard in October 2025. SWE-bench is the benchmark that drops models into real GitHub repositories and asks them to fix actual bugs. This is not a toy coding test. The model must navigate a full codebase, understand the issue from a GitHub ticket, identify the relevant files, and produce a working patch. In 2023, the best AI systems could solve just 4.4% of SWE-bench problems. By late 2025, Claude Opus 4.5 reached 80.9%. For enterprise buyers evaluating AI for software development workflows, that trajectory is more relevant than overall Arena Elo.

On GPQA Diamond, the graduate-level science benchmark where PhD experts only score 65-74%, Gemini 3 Pro leads at 92.6%. GPQA Diamond contains 448 questions in biology, physics, and chemistry specifically designed to be “Google-proof,” meaning non-experts cannot answer them even with 30 minutes of unlimited web access. The fact that AI models now exceed human expert performance on this benchmark is itself a milestone.

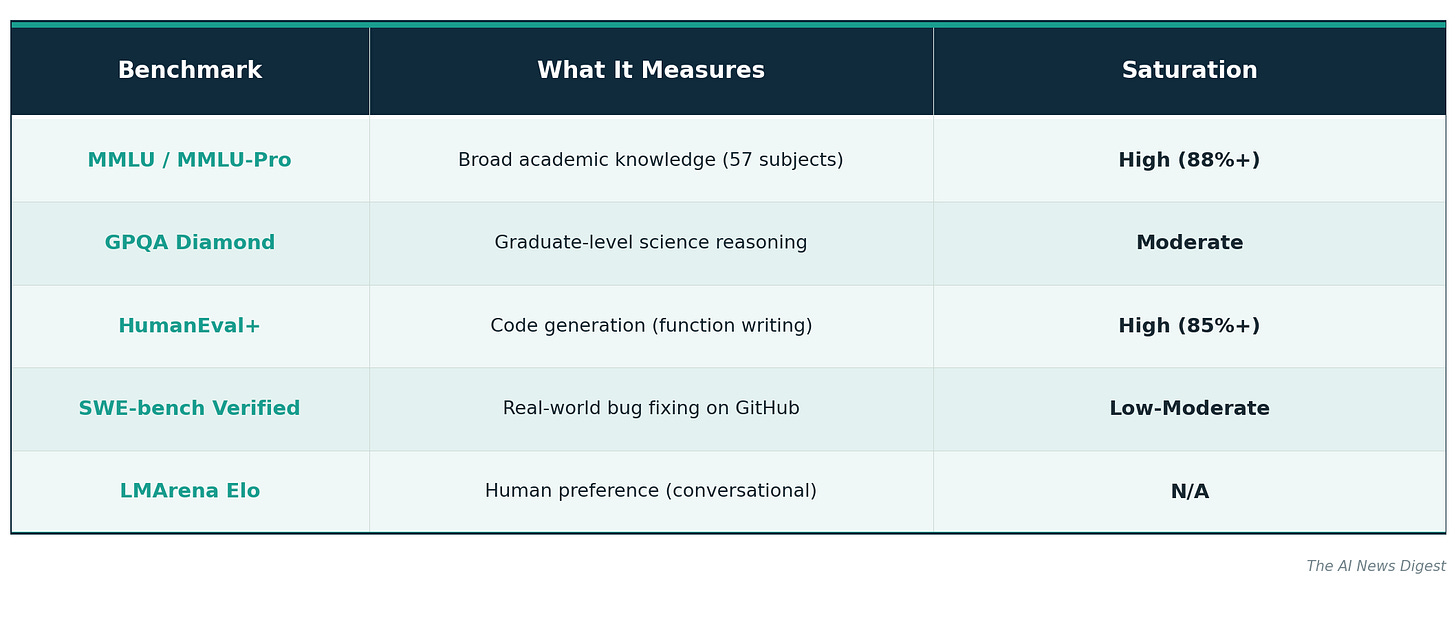

On the original MMLU benchmark (57 academic subjects, multiple-choice), the differences between frontier models have compressed to the point of irrelevance. Top models all score above 88%. MMLU was the gold standard in 2023 but is now saturated and has been largely superseded by MMLU-Pro, which uses harder questions and more answer choices.

Anthropic’s strategy has been consistent. Rather than chasing overall leaderboard position, they have focused on coding performance, reliability, and safety, the metrics enterprise customers actually weigh in purchasing decisions. Claude is the only state-of-the-art model available on both AWS and Google Cloud Platform, giving it distribution advantages that no benchmark captures.

DeepSeek V3.2 deserves mention as the economic disruptor. It delivers frontier-class performance close to GPT-5 at a cost 94% lower, which does not show up on quality leaderboards but matters enormously for cost-sensitive deployments.

The Benchmark Landscape: What Each One Measures

Understanding which benchmark measures what is essential for evaluating any model claim. Here is what the major benchmarks actually test:

MMLU was useful when models were still learning factual knowledge. It is now too easy to differentiate frontier models. HumanEval tests whether a model can write correct Python functions from docstrings, but the 164 problems are relatively simple algorithms, not production code. Most frontier models score 85%+ and the differences are noise.

SWE-bench Verified is the current gold standard for code evaluation because it uses real GitHub issues that require understanding entire codebases. It is hard to saturate because the problems are complex, varied, and representative of actual engineering work.

GPQA Diamond remains one of the few knowledge benchmarks that still differentiates. Questions are created by PhD domain experts and validated to be genuinely difficult, even for other experts in the same field.

LMArena Elo captures something none of the automated benchmarks can: whether humans actually prefer one model’s output over another in open-ended conversation. Its weakness is that preference does not always correlate with accuracy, and the user base skews toward English-speaking developers.

Why Benchmarks Are Both Essential and Broken

The benchmark landscape in 2026 has a fundamental problem: Goodhart’s Law. When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure. Model labs have become expert at optimizing for specific benchmarks without necessarily improving real-world performance.

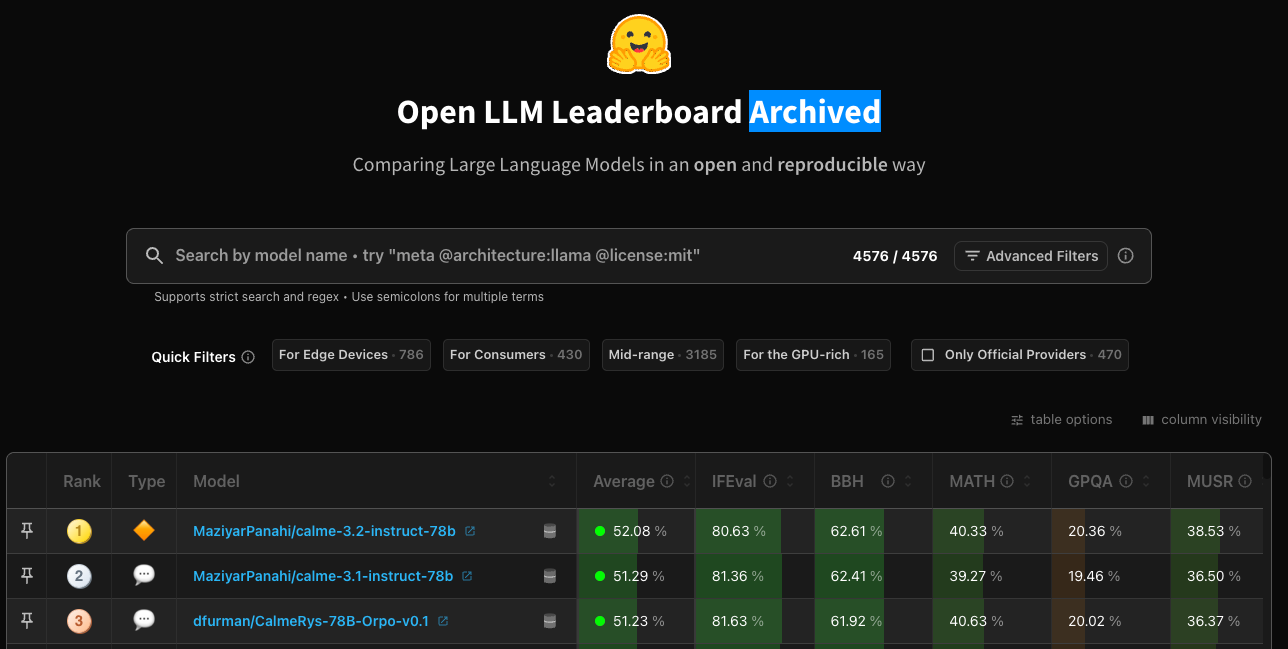

The pattern repeats across every benchmark. A new evaluation is introduced. It differentiates models meaningfully. Labs optimize for it. Scores converge. The benchmark loses discriminating power. A harder version is introduced. The cycle starts again.

LMArena’s advantage is that it partially sidesteps this problem because the prompts come from real users, not a fixed dataset. But LMArena has its own limitations. The user base skews toward technical users who value different things than, say, a marketing team or a medical researcher. The “vibes” of a response (tone, formatting, length) can influence votes independently of substance. Model labs have been accused of optimizing outputs for conversational appeal, using techniques like generating more structured markdown or more confident-sounding language, rather than improving actual reasoning.

The Business of Benchmarks

A single leaderboard position shift on LMArena can influence millions of dollars in API revenue. When a model reaches the top of the Arena, developers try it. When developers try it, enterprises evaluate it. When enterprises evaluate it, contracts follow.

This is why competition in the benchmarking space itself is heating up. Scale AI launched SEAL Showdown in September 2025, a competing leaderboard that uses a broader, more diverse evaluator base and different methodology. Scale AI brings its data-labeling expertise to bear, arguing that its evaluators can assess factual accuracy and instruction following more rigorously than LMArena’s crowdsourced votes.

Hugging Face continues to run the Open LLM Leaderboard, now in its v2 iteration, which focuses on open-source models and uses a suite of benchmarks including MMLU-Pro, GPQA, MATH, IFEval, MuSR, and BBH.

Artificial Analysis publishes an Intelligence Index that combines quality benchmarks with pricing, latency, and throughput metrics, which is often more useful for procurement decisions than pure quality rankings.

LMArena’s $100 million raise signals that benchmark infrastructure is becoming a business in its own right. The company’s challenge is maintaining neutrality while generating revenue. If the platform that ranks models also sells services to the companies building those models, the conflict of interest becomes obvious. Hugging Face faces a similar tension with its leaderboard and model hosting business.

For anyone evaluating AI models, the best approach is to treat benchmarks as one signal among many. Arena Elo tells you about broad human preference. SWE-bench tells you about real-world coding ability. GPQA tells you about scientific reasoning. Pricing and latency data from Artificial Analysis tells you about cost efficiency. No single number captures whether a model is right for your specific use case.

Use them together, trust none of them alone.

This is a phenominal analysis of how benchmarks have evolved from academic metrics to market drivers. The point about Goodhart's Law is spot on, when model labs optimize for specific benchmarks, they loose real-world utility. In my own work deploying AI systems, I've seen enterprise buyers get fixated on Arena scores without considering latency or cost tradeoffs that matter way more in production.